When Ms. Dorcas, a mother in Ghana, first learned that her daughter had dyslexia, she was shocked. At first, family members questioned whether her daughter was simply lazy or whether something Ms. Dorcas had done during pregnancy had caused the difficulty. The weight of stigma fell heavily on her shoulders. Instead of retreating, she began educating her relatives about dyslexia. Over time, their attitudes shifted from doubt to encouragement. Today, her daughter is supported by her family—a reminder that the greatest barrier is often not the learning difference itself, but the stigma and myths that surround it.

This truth was echoed across our Community of Practice. As Edward from Building Tomorrow in Uganda put it: "In our societies, negative attitudes are the biggest barrier that affects learners, more than the impairment itself." Understanding these barriers begins with examining the myths that fuel them.

The myths that hold children back

Families are usually the first to notice when something is “different” about their child. Yet what they notice is quickly filtered through community beliefs and cultural expectations. Four myths came up repeatedly in our conversations:

- “The child is lazy” – Children who struggle to read, write, or concentrate are often labelled as disobedient or slow. This judgment silences parents and shames children.

- “It’s a curse or punishment” – In some communities, learning differences are explained as anger from the gods, evil spirits, or something the mother ate during pregnancy. This places the burden squarely on mothers, who are often blamed more than supported.

- “Only doctors can fix it” – Many caregivers believe they have no role to play, waiting for medical professionals to provide solutions. This delays action and ignores the crucial support families can provide at home and school.

- “Prayer or time will cure it” – Hope is important, but when faith replaces practical action, children lose precious years of learning support.

These myths weigh most heavily on families, who face both stigma and responsibility. They are expected to carry the blame, while also being the ones who must step forward as advocates.

What caregivers need

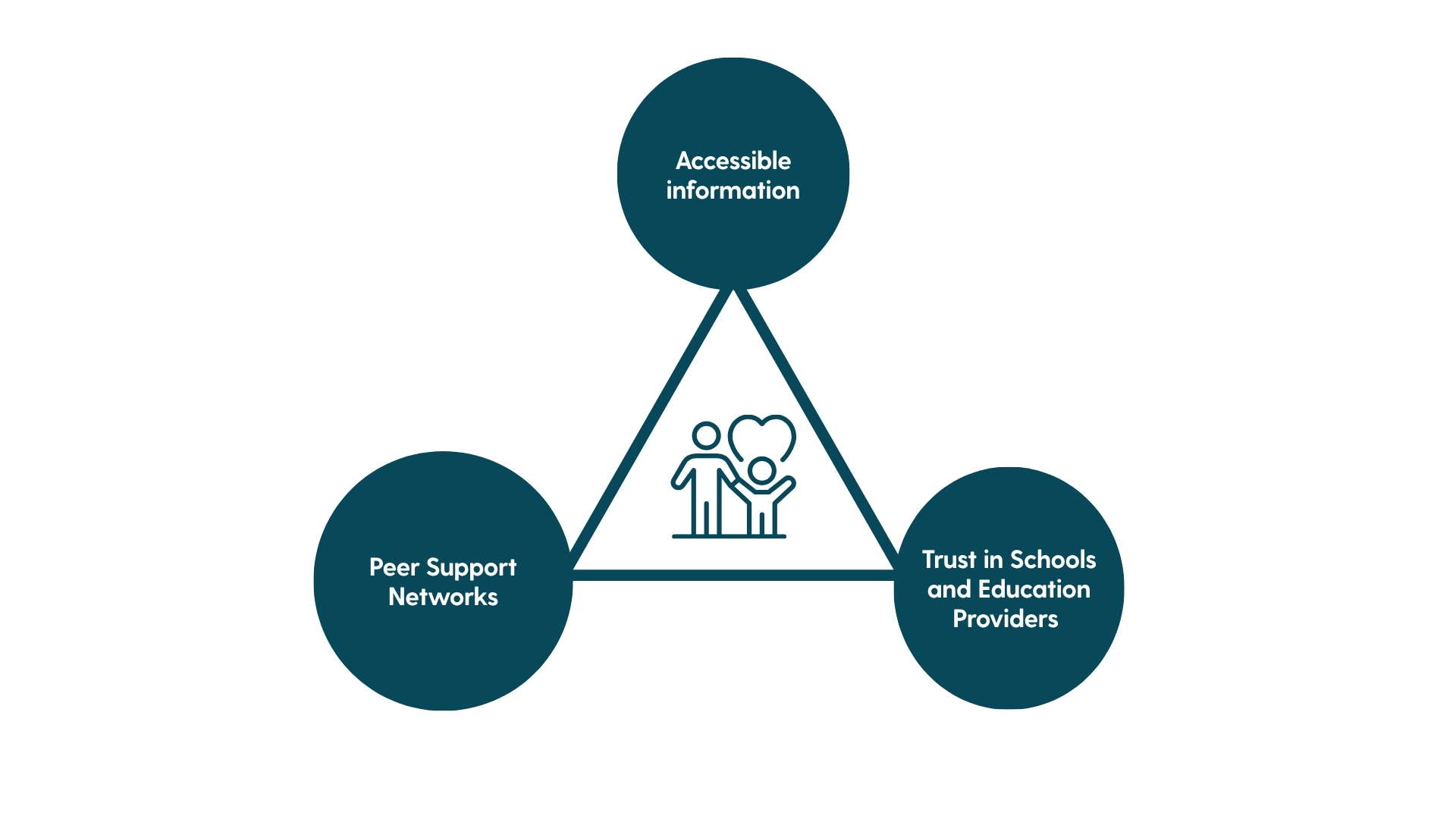

To break through myths and stigma, caregivers need:

1. Accessible Information

- Clear explanations of learning differences in local languages

- Guidance that dismantles harmful myths

- Simple, relatable formats that families can easily use

2. Peer Support Networks

- Opportunities to share experiences with other parents

- Safe spaces to reduce isolation and build confidence

- Collective problem-solving to strengthen advocacy

3. Trust in Schools and Education Providers

- Relationships built on collaboration rather than judgment

- Feeling heard and included in decisions affecting their child

- Schools as allies in supporting learning and inclusion

When these conditions are met, parents shift from silence to advocacy—just as Ms. Dorcas did for her daughter.

Putting principles into practice: Tackling stigma through families and communities

Across low- and middle-income countries, organisations are finding ways to support families in confronting myths and stigma around learning differences. While approaches differ by context, all share a focus on empowering caregivers as central actors in inclusion. When caregivers move from silence to advocacy, they create “bottom-up demand” that can influence schools and policymakers. Parent networks often become a channel for articulating community priorities, which in turn pressures local education officials to adapt school practices and drives momentum for system-wide change.

- Myth-busting and awareness raising – Families benefit from clear, accessible information that challenges harmful beliefs. In Ghana, Africa Dyslexia Organisation runs community workshops that explain reading difficulties as a learning difference rather than laziness, giving parents confidence to seek help.

- Caregiver capacity-building and school collaboration – Knowledge paired with practical skills enables parents to advocate effectively. In Nigeria, Beehive Schools equips caregivers with strategies to engage teachers and school staff, while in India, Muktangan works with both parents and teachers to help families understand their child’s learning needs and strengthen supportive classroom practices. This dual approach builds trust and empowers caregivers to actively support their child’s learning.

- Community trust-building – Direct engagement at the household level normalises conversations about learning differences and reduces stigma. In Uganda, Building Tomorrow trains community volunteers to conduct home visits, connecting families to guidance and support while encouraging open discussion about learning challenges.

- Peer support networks – Safe spaces allow caregivers to share experiences, reduce isolation, and collectively problem-solve. Learning Differently,Kenya creates parent circles where families exchange strategies, replacing blame and shame with solidarity and actionable solutions.

- Embedding caregiver voices in systems – Families’ perspectives inform school practices and policies, making inclusion more sustainable. In Malawi, Link Education works with schools and government partners to integrate caregiver input into inclusive education strategies, ensuring that advocacy at the household level is reinforced by systemic support.

Together, these approaches show that while stigma runs deep, it is not permanent. With knowledge, solidarity, and trusted allies, families across contexts can become powerful champions for their children’s learning and inclusion.

Bridging to systems: Making change sustainable

These community-driven efforts are vital starting points. They demonstrate what's possible when families are equipped and supported. But as powerful as they are, community-level changes remain fragile without supportive structures. Without coherent policies, adequate resources, and institutional commitment, families like Ms. Dorcas's continue to struggle in isolation. True inclusion requires system-wide alignment across multiple levels of policy and practice—ensuring that the courage of individual parents is met with structures that can sustain and scale their efforts.

While policies often articulate a vision for inclusion, the real test lies in translating that vision into classroom practice. Without coherence between policy and practice, inclusive education risks becoming a paper exercise. Non-state actors, ranging from nonprofits to private sector partners are often the engines of innovation in education. They test new ideas, demonstrate what works, and build momentum for scaling. For inclusive education to move beyond pilot projects, it must be embedded into government structures and budgets. This ensures that programs are not dependent on donor funding or short-term initiatives but are part of long-term commitments.

Two examples illustrate this approach: Simple Education Foundation (SEF) collaborates closely with government institutions like State Council of Educational Research & Training (SCERT) and the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET), bringing together government systems with private expertise to redesign teacher training modules and strengthen classroom practice in India. FANA Ethiopia, on the other hand, complements Ethiopia's inclusive education framework through in-service teacher training, adapted curricula, and community sensitisation to ensure that policy becomes actionable. These partnerships ensure that innovations are not confined to small pockets but are mainstreamed into state systems.

Building on these government-nonprofit partnerships, another critical dimension emerges: cross-sectoral coordination. Education systems cannot operate in a silo; they must collaborate with both the social protection and health sectors to ensure continuity of support. Joint programming between ministries of health, education, and social welfare can enable integrated support packages—from medical screening and diagnosis in early years to targeted educational support and scholarships for learners with learning differences. This holistic approach ensures that the child is seen as a whole person, and that interventions reinforce each other rather than operate in isolation. (UNICEF, 2015)

Mindset shifts take time – Systems help bridge the gap

Reducing stigma is not a one-off awareness campaign—it is a long process of engagement and trust-building. Language changes, like referring to a child as “a child of her age” instead of “a normal child,” may seem small, but they help communities move from judgment to understanding.

This is where the connection between community action and systems support becomes most visible. Caregivers, especially mothers in marginalised settings, can become the strongest champions for inclusion when stigma is addressed head-on. As families like Ms. Dorcas's find their voices, children with learning differences gain not only acceptance but also the encouragement to thrive. When communities understand that inclusion is about dignity and equality, they develop stronger ownership of the agenda. This ownership, in turn, pressures schools and governments to deliver on their commitments.

The outcome is not just access to education but meaningful learning for all children, including those with learning differences. By aligning policies, systems, and communities, we can move beyond fragmented initiatives toward true system-wide impact—an education ecosystem where dignity, equity, and quality are the norm, not the exception.