In a classroom in Nairobi, a teacher notices a student doodling during a writing exercise. The child isn’t defiant—they have dysgraphia, a learning difference that may make handwriting painful. Too often, such struggles go unseen.

Globally, an estimated 240 million children under the age of 18 live with disabilities (UNICEF, 2019). These include physical, sensory, cognitive, and neurological differences that affect how children grow and learn. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), children with disabilities are 49% more likely to have never attended school than their peers without disabilities, and those who do enroll often face barriers in schools and systems that impede learning and participation. Despite the scale of the problem, most teachers have little training in supporting children with disabilities. For example, in many LMICs, fewer than one in ten teachers have received any preparation on how to support children with disabilities (UNESCO, 2020).

Within this broader group are millions of children with cognitive and neurological differences that specifically affect learning—commonly referred to as learning differences. Data on these conditions is especially scarce, and the true scale is likely much higher than reported. In classrooms across LMICs, countless children experience learning challenges that are neither recognised nor adequately supported. They may struggle to read, write, maintain focus, or keep pace with their peers. Too often, they are labelled unmotivated or disruptive when, in reality, they have specific learning differences that influence how they engage with learning tasks. (WHO & World Bank, 2011; UNESCO, 2020).

These differences—sometimes visible, but often not—affect millions of children. To better understand these challenges and identify promising approaches, Global Schools Forum is conducting a scoping study on learning differences in LMICs. This blog shares insights and lessons emerging from the study.

What do we mean by learning differences?

Learning differences include a wide range of conditions that affect how children absorb, process, and express knowledge. They are frequently unrecognised and misunderstood, especially in under-resourced settings where screening tools, specialised personnel, and inclusive teaching strategies remain limited (UNICEF, 2019).

“You cannot tell just by looking at a child. These children often appear inattentive or unmotivated, but their brain simply works differently.” – Phyllis Munyi, Founder and Executive Director of Dyslexia Organisation, Kenya

For the purpose of this study, we are defining learning differences broadly to include both diagnosed and undiagnosed learners who experience academic, behavioural, and/or social-emotional challenges in classrooms. The focus is on children aged 6 – 18 years in LMICs attending government or low-fee private schools, where specialised support and inclusive resources are often scarce.

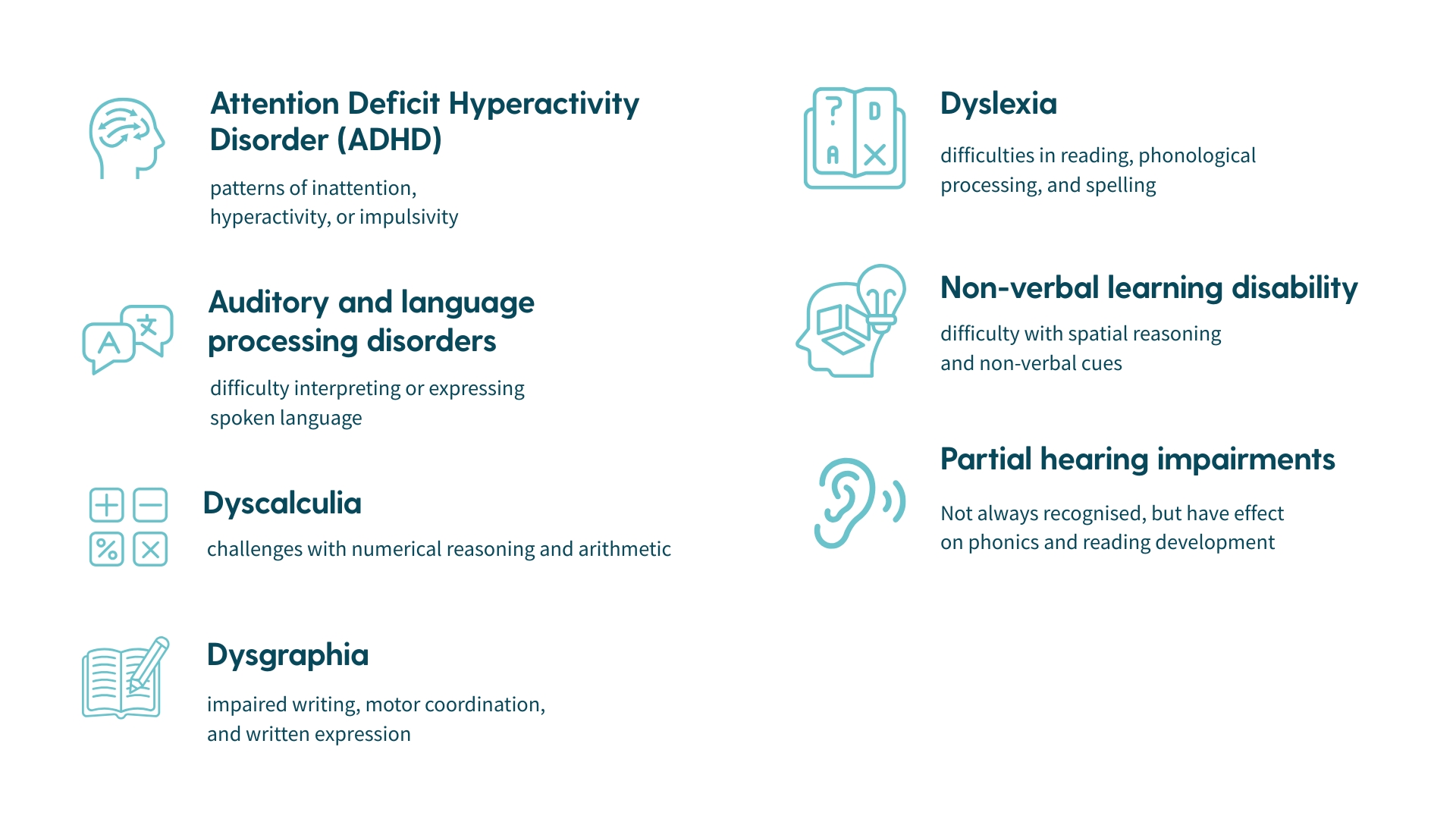

In our scoping study with practitioners and organisations across LMICs, the following types of learning differences were most frequently identified. This is not an exhaustive list but reflects the conditions most commonly encountered by education providers¹:

Why Early Identification is a Game-Changer

Research shows that early diagnosis and support improves academic progress and helps reduce the impact on learning difficulties as the student advances in school. Moreover, untreated learning differences—particularly among children in low-income settings—are associated with lower school completion rates, limited employment opportunities, and increased risk of mental health challenges (National Academies of Sciences, 2015; Reed et al., 2022).

Our scoping study highlights the early primary years (ages 6-10) as a critical window for identifying and supporting children with learning differences. This is when foundational literacy, numeracy, and classroom behaviours are taking shape and when targeted intervention can make the biggest difference.

Despite this, most LMIC systems wait until “failure,” intervening only when a child’s performance drops significantly. By then, the child may already feel excluded, discouraged, or stigmatised. Older students, particularly those aged 14 and above often struggle to meet rising academic expectations without ever having received targeted support, highlighting the need for remediation, career guidance, and skill-building opportunities.

Key findings from our scoping study

GSF’s approach to this work is grounded in research and practitioner insights. Over six months, we conducted:

- A scoping study of evidence on learning differences in LMICs

- Focus group discussions with education providers and caregivers

- Community of Practice sessions with organisations globally

- Consultations with experts in inclusive education

Across these engagements, several themes emerged as critical enablers of inclusion:

- Early identification, screening and diagnosis

Many children remain invisible because there are few affordable, culturally relevant tools to detect learning differences early. Early screening helps teachers and families understand a child’s needs before gaps widen and stigma takes hold. - Teacher capacity building

Most pre-service and in-service training focuses narrowly on physical impairments, leaving teachers without the tools or confidence to recognise and respond to learning differences. Building skills and ownership is essential for inclusion to become routine practice. - Inclusive classroom practices

Creating inclusive classrooms goes beyond awareness. It requires practical strategies—like differentiated instruction, formative assessments, low-cost learning aids—to meet diverse learner needs every day and track progress meaningfully. - Family and community engagement

Caregivers are a child’s first and most important allies. However, families frequently lack accessible information, and cultural stigma can discourage them from seeking help. Engaging caregivers and communities helps build shared understanding and sustain support beyond the classroom. - System enablers

Even where inclusive education is a policy goal, implementation often stalls without adequate funding, clear accountability, or effective partnerships. Strengthening systems—from referral pathways to financing—helps ensure promising approaches can grow and reach more learners.

These insights from our scoping study highlight both the urgency of the challenge and the opportunity to act. In the subsequent blogs in this series, we will explore practical strategies and examples of how education providers can build more inclusive systems and classrooms.

A call to action

Children with learning differences are a part of every classroom, school, and community. It is essential to deliver on the promise of education for all. Whether you are a school leader, a teacher, a funder, or a policymaker, you have a role to play. Together, we can share effective and adaptable models and tools that are making a difference, and build a stronger evidence base for inclusive, community-led solutions.

By working collectively, we can ensure that all children have the support they need to thrive—valuing not just whether they learn, but how they learn.

References

- Global Schools Forum scoping study on Learning Differences

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015). Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children.

- Reed, K., Calhoun, S., & Wood, B. (2022). Prevalence and impact of learning disabilities: A public health perspective. Frontiers in Public Health.

- UNESCO (2020). Global Education Monitoring Report: Inclusion and Education.

- UNICEF (2019). Every Child Learns.

- WHO & World Bank (2011). World Report on Disability.

Inclusive Education

Inclusive Education