In a lively grade two classroom nestled in rural Uganda, Ms. Achieng takes on the challenge of teaching a crowded class of forty-five eager young minds. Among these students, five face significant hurdles that make it difficult for them to keep up with their peers. For some, the challenge lies in decoding words; they can sound out the letters but struggle to understand the underlying meanings. Others face even more fundamental obstacles, as they have not yet learned to recognise letters at all. Ms. Achieng is a trained teacher with profound passion for her work and for her students but lacks knowledge of identifying children with learning differences and incorporating inclusive learning practices in her day-to-day teaching. What is the role of her school leadership, community, and the government at large?

School culture is where inclusion lives

Education systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face the dual burden of increasing access and ensuring quality, particularly for children with learning differences. Debates exist on the role and efficiency of inclusive education especially for students with learning disabilities (Ford, 2013). The least restrictive environment (LRE) mandate in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) makes clear that educating children with learning differences in inclusive classrooms is preferred, unless their disability is so severe it cannot be addressed in the general education classroom even with supplementary aids and services. (NCLD, 2024)

Whereas policies and programmes play an important role, real inclusion thrives in school culture: the daily tone, behaviors, and unspoken rules that shape a child’s experience of belonging. When a teacher raises an eyebrow at a slow reader, when bookshelves carry only “average” learner stories, or when a student never sees someone like them as a classroom hero—these shape exclusion more than any lack of infrastructure. Building teacher capacity is essential not just for technical instruction, but for embedding inclusion into the cultural fabric of every classroom, school and community by extension.

In this blog, we explore how educators and school leaders can foster inclusive school cultures, grounded in empathy, student voice, and adaptive practices. Through evidence-based tools like the Learning Variability Navigator, and strategies like Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Empathy Interviews, we present a roadmap to make inclusion not just possible, but transformative. We also highlight the role of the teacher and how they can be better equipped to support these children at their own level.

What is school culture and why does it matter for inclusion?

School culture is the invisible but powerful set of norms, beliefs, values, and attitudes that influence everything from how students are greeted in the morning, what is said (and not said) in classrooms and corridors, how students are celebrated (or stigmatised), to how teachers interact with each other and with students, and even to how disciplinary actions are applied. Inclusion, therefore, is not limited to enrolling children with learning differences and terming them as inclusive schools, it is about making sure every student feels they belong, they are valued, and they have the tools to succeed.

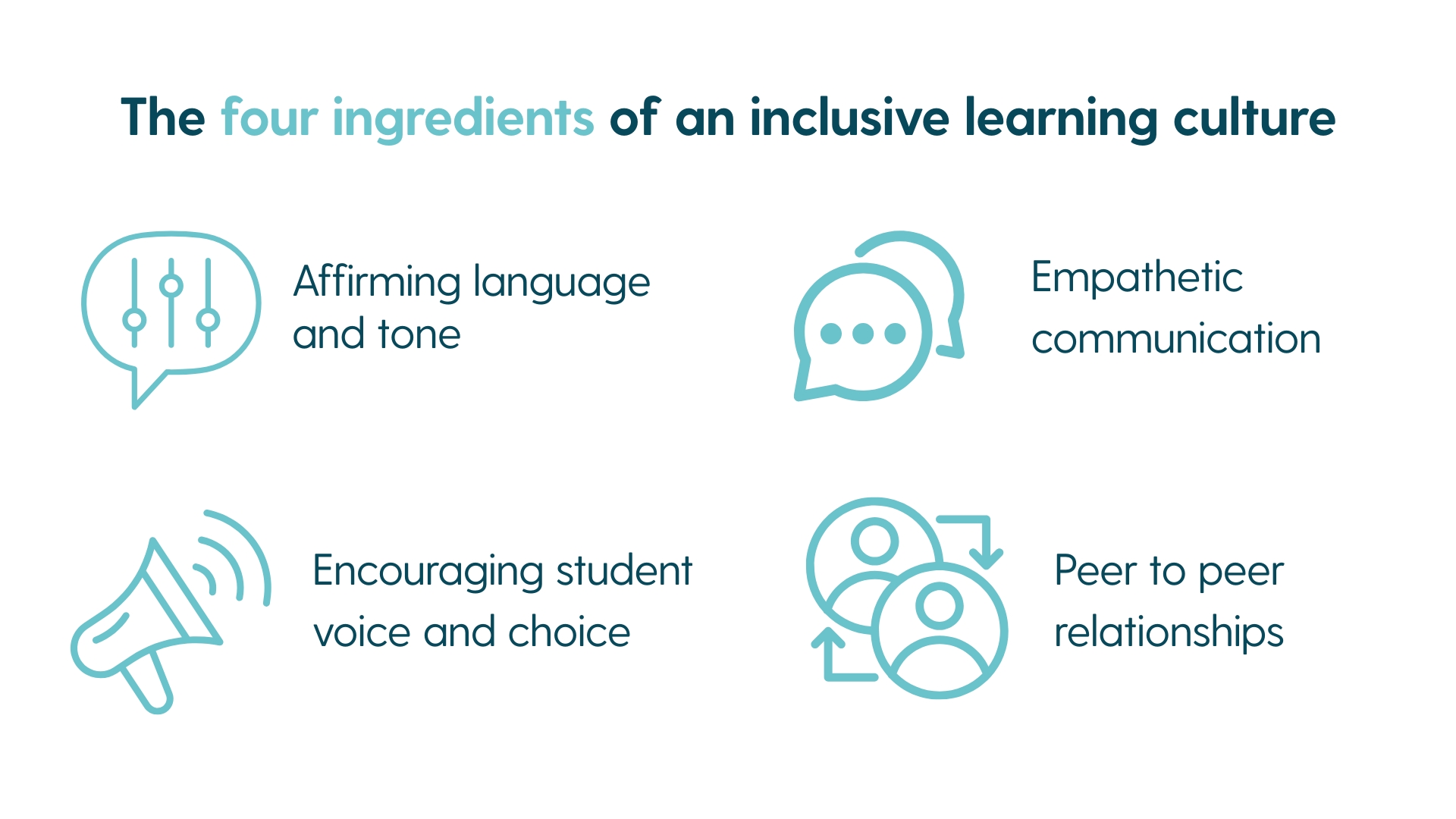

What are some of the key ingredients towards nurturing inclusive learning?

When classrooms are intentionally designed for inclusion and accessibility, they enhance learner focus, motivation, and well-being. Flexible seating, sensory elements, and culturally responsive layouts support attention, self-regulation, and belonging. Thoughtful use of space—collaborative zones, quiet areas, and visual support foster engagement across diverse needs. Inclusive environments that reflect students’ identities, integrate music and movement, and ensure emotional safety boost creativity, memory, and executive function. Consistent lighting, reduced noise, and physical comfort reduce cognitive load. By removing barriers, inclusive design empowers neurodivergent, multilingual, and diverse learners to participate fully - nurturing curiosity, confidence, and a strong sense of belonging for every student.

1. Affirming language and tone: When teachers use phrases like, “You learn in a different way, and that’s okay,” or “Let’s try it a different way,” they communicate that all learners are capable, thereby encouraging curiosity instead of labelling it ‘difficulty’, ‘stubbornness’ or being ‘slow’, and transforming classroom dynamics. In the Literacy 4–6 Factors section of the Learning Variability Navigator (LVN), factors like Background Knowledge, Language, and Executive Function show how variable student needs can be and why affirming language is essential. LVN takes a holistic approach to include factors of learning on student background, social and emotional skills, cognitive factors and academic content. Because LVN shows how factors are interconnected, it also can help teachers better understand the “why” behind a student’s behavior and select appropriate strategies to address the student’s unique needs.

2. Empathetic communication: Being the people who spend the most time with the students in a day, teachers can create a safe environment for the students, particularly those with learning differences to share their experiences and express themselves. Empathy interviews help an educator to ask the right questions and actively listen to learn about students' experiences and identity beyond the classroom walls and how that intersects with their school experience. Through these conversations, teachers gain an insight into the challenges students face, their strengths, and their sense of belonging in school.

3. Encouraging student voice and choice: Providing students, particularly those with learning differences, the chance to express how they learn most effectively is crucial in fostering a sense of agency. When students are empowered to choose their preferred methods for demonstrating their understanding—whether through drawing, speaking, acting, or other modalities, they are more likely to feel in control of their learning journey. This personalisation not only highlights their unique strengths but also encourages deeper engagement. By accommodating different learning preferences, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive environment where each student can thrive.

4. Peer-to-peer relationships: Classrooms become inclusive when peer support is normalised. Inclusive pedagogy, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) strategies, enhance learning for everyone; by offering multiple ways for students to engage with content and understanding, while teachers unlock potential in every child. Whereas no child’s brain works the same way, learner variability is predictable and the UDL guidelines help educators address the variability of each learner in three main categories – Engagement, which is the child’s motivation of learning and interest; Representation, representing the what of learning including perception and language, and the Action and Expression, the how of learning, that is physical action and communication.

Equipping teachers to lead the journey towards inclusion

In every classroom, teachers stand on the frontlines of learning and often, they are the first to notice when a child is struggling. Teachers are not just content deliverers—they are observers, guides, and connectors. Whether it is a difficulty with reading, challenges in concentration, or a unique way of processing information, their proximity to students allow them to spot early signs of learning needs, but too often, they lack the tools to act. As Archana Rao from Perkins India puts it, “Teacher's knowledge, skill, and abilities help to strengthen the contributions of the community, family, school, and government policies, and vice versa. This exchange of learning further impacts the learning outcomes of the student itself”

Despite growing awareness, the challenges to inclusive teaching remain steep. Overcrowded classrooms, social stigma, and a lack of practical training leave many teachers overwhelmed. Many feel unprepared to adapt their teaching and isolated in their efforts. To shift this, governments and education partners must invest more in pre-service preparation and in-service training—not just in theory, but in practical strategies that teachers can apply the next day. Within the pre-service level, there has been a focus on physical disability mainly when it comes to special education, with teachers graduating with little to no knowledge of learning differences. Inclusive education begins by equipping teachers through practical training, so they can recognise, refer to, and respond appropriately. Ongoing professional development, peer mentoring, and coaching models are essential for maintaining inclusive practices, not just as one-off sessions, but as part of teachers’ professional journey.

For accurate and sustainable results, tools and resources must align with national curricula, be available in local languages, and reflect the realities of teachers’ classrooms. Imported materials may look good on paper but often fall short in practice. When teachers are involved in co-creating materials, the result is more practical, relevant, and sustainable. Community-based coaching and school cluster models are also promising vehicles for delivering context-sensitive support at scale.

Inclusion isn’t just a policy—it’s a practice. And at the heart of that practice are teachers. If we are serious about building education systems where every child thrives, we must start by empowering the very people who make learning possible every day. The journey to inclusive education begins in the classroom—and teachers are ready to lead the way, if we give them the tools to do so.

Building teacher capacity means equipping them not only with skills, but with a shift in perspective—from “what’s wrong with the child?” to “what can I change in the environment to support them?”

References

CAST. Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from CAST: https://www.cast.org/what-we-do/universal-design-for-learning/

Digital Promise. Learning Variability Navigator. Retrieved from Digital Promise: https://lvp.digitalpromiseglobal.org/

Ford, J. (2013). Educating Students with Learning Disabilities in Inclusive Classrooms. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education. Retrieved from https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol3/iss1/2/

LVP. Literacy 4-6. Retrieved from Digital Promise: https://lvp.digitalpromiseglobal.org/content-area/literacy-4-6/strategies/empathy-interviews-literacy-4-6/summary

NCLD. (2024). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Retrieved from National Centre for Learning Disabilities: https://ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/240502-Learn-the-Law-Individuals-with-Disabilities-Education-Act.pdf

Pape, B. (2018). Learner Variability is the Rule. Retrieved from Digital Promise: https://digitalpromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Learner-Variability-Is-The-Rule.pdf